One of the first Hong Kong people I ever consciously remember meeting was in Wellington, New Zealand in the early 1980s. I recall precisely, even now, the exact room, the early morning sunlight, the two chairs, my papers on top of the grey desk between us. I briefly worked at the Labour Department and this man was looking for a job. I interviewed him. He walked in slowly and sat with difficulty. I did not know he was Chinese. How could I? He didn’t have a face.

I went through the initial formalities of the interview. He was very friendly and open. Then, without my asking, he explained what had happened to him. Working in a plastic factory in Kowloon a decade earlier, a fire began and he was trapped. The fire, fueled by toxic chemicals and plastic, engulfed his body. He survived – just – dragged out of the inferno by fire-fighters. His face had entirely melted, and in between the blood-red of skin grafts, were four punctured holes: two for his eyes, one for his nose and one for his mouth – his ears bare canals, his hair long gone. His mouth was luckier than the rest of his face, as his lip muscles had not fused in the fire – they worked, and he could speak. But, he didn’t have a face that I could recognize as a face.

Of all the disasters that we could encounter – earthquakes, flooding, pestilence, etc. – fire is possibly the most terrifying. We are so familiar with fire; we easily light cigarettes and candles, we sit around a BBQ or campfire happily seduced by flames dying into embers, dinners are prepared over fire. But fire’s familiarity gives its potential for destruction a greater shock when it does. Or, as the great art critic Robert Hughes realized as he was trapped in his mangled car after a horrendous car accident with multiple bone fractures, a weakening pulse and drifting into traumatized shock. His biggest fear was not death, but that the car’s petrol tank would ignite and he would be engulfed by fire. Fire was his greatest fear in life; worse, he imagined, than mere death.

Fires destroying the Amazon forests in Brazil and surrounding countries and agricultural fire burn-offs in Indonesia have been recent news headlines. One hot summer, driving just north of Sydney, I encountered scattered bushfires, the main fires had burned out a day earlier, but smoke hung around and forest debris littered the roads. But the biggest implication of the violence of those fires was later that night as I walked along a beach. The sea had receded, but as far as the eye could see at the high-water mark, were five-metre high walls of burnt leaves, blown by the fires and wind into the sea and then returned to the beach by the sea’s waves. The violence of fire is frightening and contradictory: quick and slow, momentarily beautiful and suddenly ugly. The results are always, always awful – whether the damage is done to person or property.

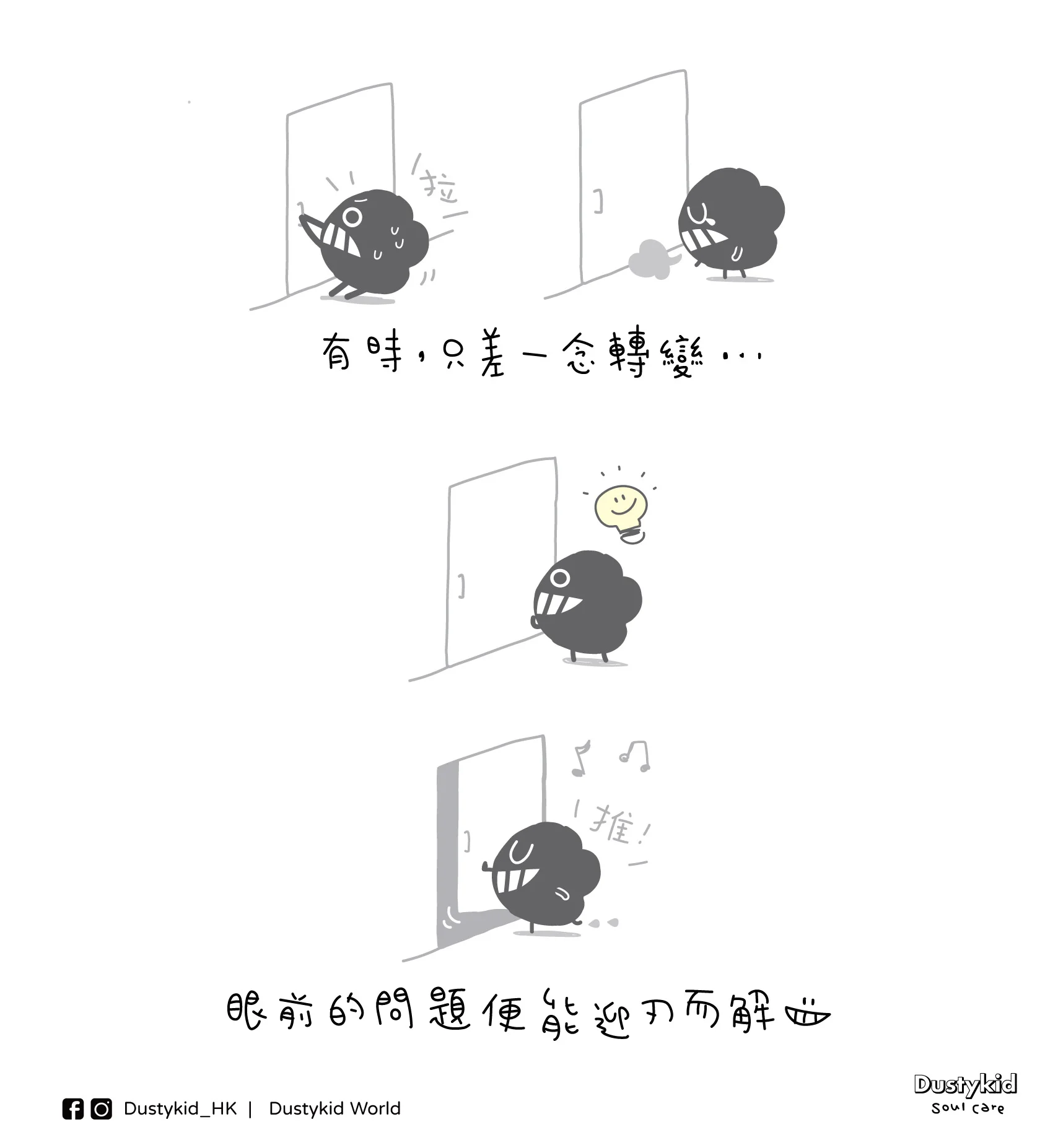

In the last weeks we have witnessed Molotov cocktails thrown and bonfires lit by protesters, meanwhile the Tai Hang fire dragon was paraded through streets for its yearly purification, but whose neighbourhood had seen tear gas and fires only a week earlier. It has been argued that this escalation of violence and the use of fire are only in retaliation to the increase of police violence towards protesters, the press, and innocent onlookers at protest sites. Violence then becomes circular: you do it, we do it too; you do it stronger, we’ll do it stronger. I have read news commentary that violence has forced the government to shelve and then withdraw their extradition legislation. This, however, is unproved. The most effective opposition – still – is in numbers: millions continually peacefully marching has an unsurpassed moral message that cannot be ignored by any government. In contrast, violent protest action, when confronted by the unending powers of the police and laws of the state, must inevitably go underground. Protest action would evolve into guerrilla action, planting of bombs and sabotage. It would look like the actions seen in Northern Ireland and the ‘collateral damage’ will involve innocent members of the public as a bomb, like fire, never recognizes neutrality.

The government can’t sit on its hands and wait or merely initiate mild “dialogue”. It is universal suffrage and fairer representation in the legislature that is the crux to resolve Hong Kong’s political crisis. That is what millions of peaceful protesters want and which will also placate the hardline protesters. If protests go underground, it will be so much harder to initiate anything.

We see on our streets the graffiti, “if we burn, you burn with us”. As graffiti this is harmless, but last year the Scottish band Franz Ferdinand played an energetic concert at Wan Chai’s Southorn Stadium with a rocking version of their song ‘This Fire’, it is too prescient for comfort: “…Now there is a fire in me / A fire that burns / This fire is out of control / I’m going to burn this city / Burn this city….”.

If it does come to that, then the protesters’ face-masks could be recycled to hide the awful scars of a miss-thrown Molotov cocktail – and believe me, a burned, disfigured face is truly awful.